Corvallis, Ore. – Scientists at Oregon State University have shown that viral infection is involved in coral bleaching – the breakdown of the symbiotic relationship between corals and the algae they rely on for energy.

Funded by the National Science Foundation, the research is important because understanding the factors behind coral health is crucial to efforts to save the Earth’s embattled reefs – between 2014 and 2017 alone, more than 75% experienced bleaching-level heat stress, and 30% suffered mortality-level stress.

The planet’s largest and most significant structures of biological origin, coral reefs are found in less than 1% of the ocean but are home to nearly one-quarter of all known marine species. Reefs also help regulate the sea’s carbon dioxide levels and are a vital hunting ground that scientists use in the search for new medicines.

Since their first appearance 425 million years ago, corals have branched into more than 1,500 species. A complex composition of dinoflagellates – including the algae symbiont – fungi, bacteria, archaea and viruses make up the coral microbiome, and shifts in microbiome composition are connected to changes in coral health.

The algae the corals need can be stressed by warming oceans to the point of dysbiosis – a collapse of the host-symbiont partnership.

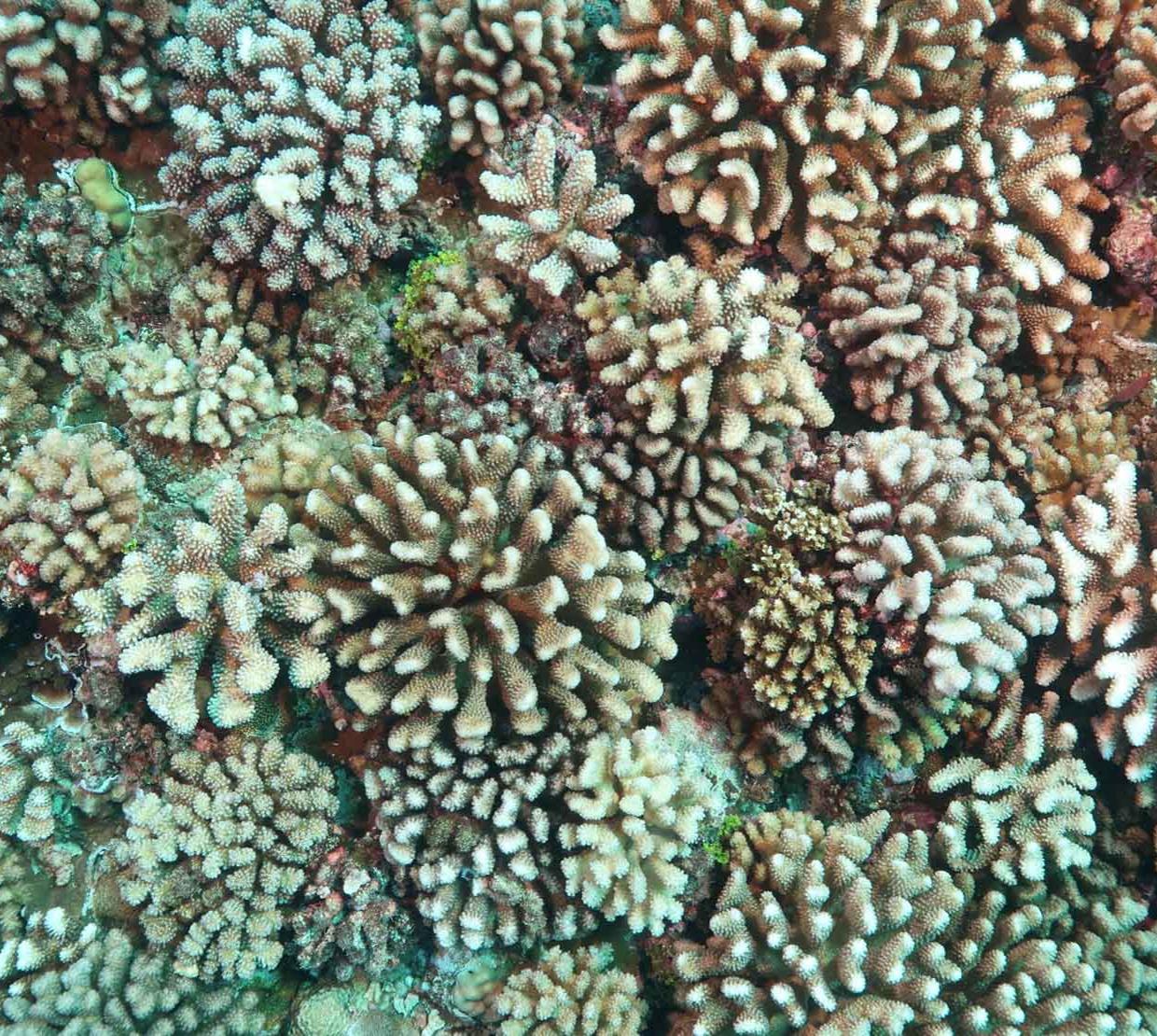

To better understand how viruses contribute to making corals healthy or unhealthy, Oregon State Ph.D. candidate Adriana Messyasz and coral researcher Rebecca Vega Thurber in the Department of Microbiology led a project that compared the viral metagenomes of coral colony pairs during a minor 2016 bleaching event in Mo’orea, French Polynesia.

Also known as environmental genomics, metagenomics refers to studying genetic material recovered directly from environmental samples, in this case samples taken from a coral reef.

For this study, scientists collected bleached and non-bleached pairs of corals to determine if the mixes of viruses on them were similar or different. The bleached and non-bleached corals shared nearly identical environmental conditions.

“After analyzing the viral metagenomes of each pair, we found that bleached corals had a higher abundance of eukaryotic viral sequences, and non-bleached corals had a higher abundance of bacteriophage sequences,” Messyasz said. “This gave us the first quantitative evidence of a shift in viral assemblages between coral bleaching states.”

Bacteriophage viruses infect and replicate within bacteria. Eukaryotic viruses infect non-bacterial organisms like animals.

In addition to having a greater presence of eukaryotic viruses in general, bleached corals displayed an abundance of what are called giant viruses. Known scientifically as nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses, or NCLDV, they are complex, double-stranded DNA viruses that can be parasitic to organisms ranging from the single-celled to large animals, including humans.

“Giant viruses have been implicated in coral bleaching,” Messyasz said. “We were able to generate the first draft genome of a giant virus that might be a factor in bleaching.”

The researchers used an electron microscope to identify multiple viral particle types, all reminiscent of medium- to large-sized NCLDV, she said.

“Based on what we saw under the microscope and our taxonomic annotations of viral metagenome sequences, we think the draft genome represents a novel, phylogenetically distinct member of the NCLDVs,” Messyasz said. “Its closest sequenced relative is a marine flagellate-associated virus.”

The new NCLDV is also present in apparently healthy corals but in far less abundance, suggesting it plays a role in the onset of bleaching and/or its severity, she added.

In addition to Messyasz and Vega Thurber, the collaboration included Stephanie Rosales of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Adrienne Correa of Rice University; and Ryan Mueller, Teresa Sawyer and Andrew Thurber of Oregon State.

Findings were published in Frontiers in Marine Science.